STONEMAN'S RAID: SALISBURY AND THE YADKIN RIVER BRIDGE

Facing the Yanks at Grant's Creek

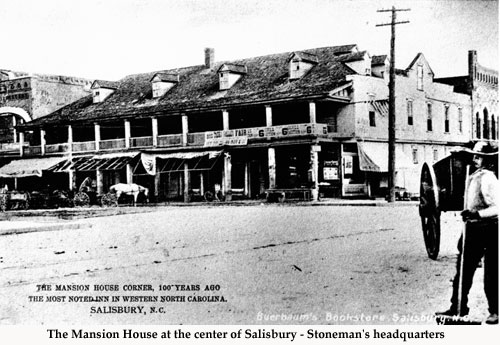

The people of Salisbury awoke

at first light on April 12, 1865. The distant sounds of

exploding artillery shells announced that Stoneman's dreaded raiders

had, at last, reached their doorstep. The Yadkin House

[Mansion House] hotel shook with every volley, and the glass window

panes shattered.1

This day, and part of the next, would be the most terrifying they would

ever know. As Margaret Beall Ramsey later recalled, "Truly

'the despot's heel was at the door.'"2 The people of Salisbury awoke

at first light on April 12, 1865. The distant sounds of

exploding artillery shells announced that Stoneman's dreaded raiders

had, at last, reached their doorstep. The Yadkin House

[Mansion House] hotel shook with every volley, and the glass window

panes shattered.1

This day, and part of the next, would be the most terrifying they would

ever know. As Margaret Beall Ramsey later recalled, "Truly

'the despot's heel was at the door.'"2

For months, Salisbury had

braced for the invasion of Union troops. William T. Sherman

was marching through the eastern part of North Carolina. Time

would tell that Joseph E. Johnston would surrender at Bennet Place on

April 26th, and that Sherman would not reach the Piedmont.

Stoneman would. Major General George Stoneman,

an imposing figure, commanded the Union army's "District of East

Tennessee". At the head of a cavalry force numbering 5,000 to

6,000, he left the Knoxville, Tennessee area on March 21, 1865, headed

for western North Carolina and southwestern Virginia. His

objective was to destroy Confederate supplies and supply lines - the

East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad, the North Carolina

Railroad, and the Danville-Greensboro line.3 From the beginning, Stoneman had Salisbury, the fifth largest city in North Carolina4,

in his sights. The overcrowded, death-ridden Confederate

Prison here was infamous, and Stoneman saw himself as the hapless

prisoners' liberator. The Confederate arsenal and store

houses were irresistible targets. And the Federals had waited

a long time to destroy the vital railroad bridge over the Yadkin River.5 Stoneman had edged closer and

closer as his forces raided Boone and Wilkesboro. From there,

they headed north toward Virginia. This unexpected move

precipitated a change in the defenses of the North Carolina

Confederates. Troops which had been sent to defend Salisbury

were moved out to cover Greensboro and Danville. General

P.G.T. Beauregard, Johnston's commander in western North Carolina, was

so confused by Stoneman's maneuvers that he thought the latter two

cities to be targets up until the time Stoneman entered

Salisbury. On that very day, Beauregard ordered 1000 soldiers

to Salisbury, but they would arrive too late.6 "On April 9 - the day of

General Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House - the bulk of

Stoneman's command reunited in North Carolina."7

Out of touch owing to the destroyed telegraph lines, from Germantown,

north of present Winston-Salem, he detached Palmer's brigade east of

the Yadkin to destroy stores and railroad lines in Salem and around

High Point and Lexington. Stoneman, with the main force of

about 4000, crossed the Yadkin at the Shallow Ford and moved down the

west side of the Yadkin through Mocksville. The night of

April 11th found them twelve miles north of Salisbury, unstoppable in

their southward march.8 By first light (5:30 am),9

Stoneman, with Miller's and Brown's brigades and the artillery, found

themselves opposed by a rag-tag assemblage of Confederates at Grant's

Creek, about 2 and 1/2 miles north of Salisbury. While

Stoneman estimated the Confederate force at 3,000,10

local accounts place no more than 500 there, including 200 "galvanized"

Irish recruited from the Federal prisoners, invalid soldiers gathered

from the hospitals, junior reserves, local citizens, and even a few

non-military Confederate government employees.11 Barrett estimated their number at between five and eight hundred.12

Brigadier General Bradley T. Johnson, Salisbury's commander, had been

called to Greensboro, and command fell to Brig. Gen. William M. Gardner

and John C. Pemberton, defender of Vicksburg. They did have

the terrain, some breastworks, and 18 artillery pieces to their

advantage.13 The Blue and Gray faced each

other at the old (Old Mocksville Road) and new (West Innes Street)

Mocksville road crossings of Grant's Creek, and at the Statesville Road

crossing,14

where Confederates had removed the planking of the bridges.

As artillery and rifle fire filled the air, in the distance could be

heard trains heading west and south from Salisbury. The

Confederates were evacuating their supplies!15 Not to be denied another escaping train, Stoneman ordered troops 2 1/2 miles up Grant's Creek.16

This distance, measured from the Old Mocksville Road, would take them

to the railroad bridge over the creek and the Old Plank Road

beyond. Here they stopped another fleeing train, finding the

sword, uniform, papers and family of slain Confederate Lt. Gen.

Leonidas Polk.17 Meanwhile, other Yankee detachments crossed Grant's Creek farther downstream.18 Outflanked on both sides, two hours19

after the first shots at Grant's Creek were fired, the Confederates

were routed, and a running battle moved toward and into the streets of

Salisbury.20

Given their positions at the creek and contemporary accounts,

Stoneman's raiders, four deep, entered down three roads: the

Old Mocksville Road and Shober's Bridge on Henderson [North Ellis]

Street, West Innes Street, and the Old Plank Road.21 It must have seemed to the residents of Salisbury that the Yanks were coming from all directions!

The Seizure of Salisbury

Margaret Beall Ramsey, a young

widow, like many other Salisbury women whose husbands were away or

dead, was alone with her three children and a few servants.

Looking out her second story window, she described "missles ... flying

thick and fast around and upon the house. ... Thousands of cavalrymen

were in hot pursuit of our Confederate soldiers, through yards, gardens

and fields on to the Town creek [south of Salisbury]."22

Harriet Ellis Bradshaw echoed,

"The roadway was jammed with a surging mass of mounted soldiers and

rampant horses spurred to a breakneck speed to overtake General

Beauregard's withdrawing troops. It was frightening,

curiously thrilling, to see the capless cavalrymen standing erect in

their stirrips as they rode, brandishing bared sabres in hand as they

let out earsplitting yells." 23 As Stoneman's Raiders reached

the center of town, "The Mayor of the town stood on the corner of the

street in front of the hotel, holding the flag of truce in his hand, up

high over his head. Along came one of the Yanks, waving his

sword and cut down the flag, howling and swearing at the top of his

voice."24 Capt. Frank Y. MacNeely, who

had returned to Salisbury, was shot and

killed. Lt. Stokes of Maryland shot Capt. Edwards25

one of the Union officers who charged him. He fled, pursued

by Union soldiers. Reining in his horse suddenly, one of them

passed him, only to be the second to die by the Lieutenant's

gun. Stokes then made good his escape.26 Civilians fled with their

belongings and flooded the road south toward Gold Hill. "In a

short time, [the road] was strewn with harness, bags, and other things."27

Years later, J. J. Bruner, the editor of the Carolina Watchman,

admitted that he "'lit out' that morning, after the town was given up,

and only saw things from a hill top on the south side of town creek.'"28

The Carolina Watchman presses were destroyed by the Raiders, and the

paper did not resume publication until the following January.29 Beyond Town Creek, the

Confederates lost their pursuers and vanished into the woods.

From there, they made their way to join York's forces above the

Yadkin. Bradshaw related, "The rebel troops quitted

Salisbury, fell back to a new position to defend a railroad bridge

spanning the Yadkin River."30 As the last of the Confederate

soldiers disappeared, the federals pitched camp on "Murphy's Woods",

later called "Herrington Heights", across Town Creek from

Salisbury. They built a large officers' quarters of pine

poles chinked with mud, as well as bake ovens.31 Having driven all Confederate

defenders from Salisbury, Stoneman began the work of

occupation. Miller's brigade was sent to destroy the railroad

bridge over the Yadkin River, six miles east of town.32 It fell to Simeon Brown's brigade to destroy everything in Salisbury that supported the Confederate cause. Foremost to Stoneman was the

liberation of the prisoners at the Salisbury Prison. Unknown

to him, all but those too sick to travel had been shipped out to

Wilmington and Richmond in February, and the prison itself had become a

storehouse.33

All that remained was for the Raiders to burn the buildings.

"No one was sorry when the Yankees made a bonfire of the evil-smelling

empty, dolorous prison, the scene of so much unalleviated suffering and

so many deaths. This chapter could only be appropriately

closed in a purification by fire."34 Before they would leave, the

Raiders would burn the prison, barracks, hospitals and surrounding

buildings used by the Confederate government; the arsenal, steam

distillery, and buildings used by the Central and Western

Railroads - office, passenger shed, car shed, 2 freight depots, large

machine shop, several steam and locomotive engines. An

expensive private tannery was also burned.35 A fire was put out before it destroyed the Rowan county courthouse and all its records.36 Stoneman's second-in command,

Brig. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, recorded "from the

preceding afternoon up to [2:00 p.m. on the

13th], the air had been constantly rent by the reports of

exploding shells and burning magazines. For miles around the

locality of the city was marked during the day by a column of dense

smoke, and at night by the glare from burning stores."37 "The great conflagration was

seen at a distance of 15 miles, and explosions of shells and kegs of

powder conveyed the impression to many anxious watchers many miles away

that fierce battle was waging."38 Indeed, the fire and explosions were reported 25 miles away in Statesville.39

A. M. Rice of Unity Township recalled his mother waking the

children. "Look out the window, the Yankees are burning

Salisbury."40 Throughout the day, Union

soldiers and camp followers went from house to house, searching through

every room, closet, and drawer. Amidst threats, they took

food and liquor. They demanded silverware and pocketwatches,

but found few valuables, which had been hidden away.41

Dr. Summerell's wife had buried her silver spoons in old shoes

underneath a row of grapevine cuttings. The doctor had taken

his pocketwatch, in the toe of a sock, to one of his patients at the

County poorhouse. She had sewn it inside her skirt.

Horses were taken to the woods behind Macay's millpond.42

Mrs. Francis E. Shober, of North Fulton Street, according to the family

Bible, had given birth to a baby boy "Born on the fateful day of

Stoneman's visit." Within the folds of the baby's diaper she

had hidden her most valuable possession, a diamond

ring. The family silver had been buried

among the ties of the nearby railroad tracks.43

Decades later, county records were found concealed in the walls of the

courthouse. Many of Salisbury's citizens asked General

Stoneman for protection, which he granted when he could. The

home where Harriett Ellis Bradshaw was a child of eight, ransacked

earlier in the day, had been given a guard. When the guard

left, he carried with him a Confederate flag "which had been hauled

down from the entrance of the Yankee prison. Fastened to a

short pole set up against the ouside frame of our front door, the flag

had rippled its rebel folds all the day long."44 In 1962, this flag found its way back to North Carolina.45 Palmer's troops, from east of

the Yadkin, arrived in the afternoon. They were sent out

again to destroy the railroad to Charlotte.46 Dr. Rumple, Mr. Wiley and his

school, James E. Kerr, "together with a long list of our best

citizens" were captured and imprisoned for the day.47 "No one thought of sleeping

that night. ... We were made to start and tremble

every moment at the terrific and unbearable explosions of shells at the

arsenal, which continued for 36 hours at least."48 By the next morning, immense

amounts of military and civilian supplies had been hauled out of every

warehouse in Salisbury and piled onto Innes and Main Streets.

In these last days of the war, Salisbury had become the "Storehouse of

the Confederacy." Supplies had been concentrated here "from

Columbia and Charlotte, Richmond and Danville. ...

Besides these, Governor Vance had deposited a large amount of state

property here."49

They filled four blocks, and were soon set afire, where they surely

smoldered for days. Poor people, both white and black,

carried away what they could.50 Miller's brigade, unable to capture or destroy the Yadkin bridge, returned to town in the morning.51 As their final act, about 2:00 in the afternoon of the 13th, the Raiders exploded the magazine and rode out of Salisbury.52 When Stoneman left,

Salisburians considered themselves fortunate, in comparison to Columbia

and Fayetteville, that the town had not been completely

destroyed. Margaret Beall Ramsey's closing comment was that

"Salisbury ... may well afford to hold Stoneman's name in grateful

remembrance."53

The Battle at the Yadkin Bridge

|

|

______________________________________________________________________

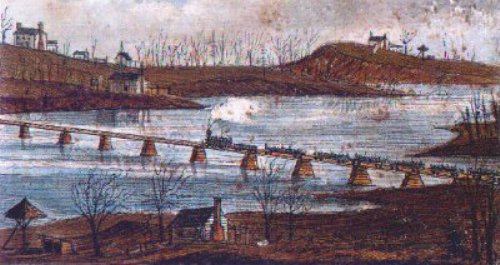

UNION PRISONERS OF WAR CROSSING THE YADKIN RIVER ON PLATFORM CARS

Toward Salisbury, N. C., February 24, 1864, Robert Knox Sneden | Six

miles east of Salisbury, the railroad bridge over the Yadkin River was

vital to rail transportation for the Confederacy, and was a

strategic target for the Union. Perhaps as early as 186354,

construction of earthen fortifications to guard it had begun.

These fortifications, on a high bluff on the north side of the river

covered the entire hill, now bisected by modern highways.

They protected the railroad bridge and Locke's (Beard's) bridge, as

well as roads east. The high bluff provided both military

superiority and a commanding view. Certainly, the

fortifications were extended in anticipation of Stoneman's arrival. In the summer of 1864, Capt.

George W. Kirk led a band of raiders from Morristown, Tennessee into

western North Carolina. "He did not accomplish the principal

object of the expedition - that is, the destruction of the railroad

bridge over the Yadkin River; but made arrangements to do this

secretly, it being impossible for him to do it by force."55 These secret arrangements may

have been with a band of deserters and Union sympathizers in Yadkin

county. On February 12, 1865, Bradley T. Johnson in Salisbury

reported: "It is said that a large number of deserters are

collecting in Yadkin [county] for an attack here. A few

cavalry will disperse them." 56 A report by Brig. Gen. Davis

Tillson, April 9, 1865, noted the importance of destroying the Yadkin

bridge: "At Boone information was received that General

Stoneman was at or near Wilkesborough, N. C., on the 30th ultimo,

moving down the Yadkin River, with the supposed intention of destroying

the important railroad bridge over the Yadkin River." Tillson

noted that if Stoneman were unable to accomplish this, his own forces

would do so.57 Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard had

prepared for Stoneman's approach. On March 31, 1865, he

ordered: "Be careful enemy do not destroy railroad bridge

across the Yadkin. Protect it with field-works. One

or two batteries have been ordered to you."58

On April 3rd he added: "Light battery at Yadkin bridge must

be placed on south side of river should proper positions be found."59

This order was re-iterated, too late, on April 12th: "Yadkin

bridge should be well guarded on both sides, especially on south side

now."60

On April 6th, Beauregard advised "the immediate construction of

tetes-de-point at railroad bridge on Yadkin and Catawba; also at

nearest fords to each said bridge."61 The fortifications were said to have been laid out "by a Lieut. Beauregard, a nephew of the late general."62 Originally known as Camp Yadkin,63 over the years they have been called Fort Beauregard,64 Fort York, and York Hill. "General [Zebulon] York of

Louisiana, with ten or twelve hundred men - Home Guards and

'Galvanized' Irish - defended the bridge."65

"York was getting well up in years, and having lost an arm he was known

by the sonbriquet [sic] of 'One Wing York.'"66 C.D. Simmerson's eye-witness account numbers the Confederate troops at 10,000,67

but Beall's estimate is probably more accurate. According to

Simmerson, Captain Frank Smith, of Alabama, and Capt. Henry Clement

commanded Confederate troops at the fort.68

"Two of the biggest Confederate cannons had been placed to control the

approaches to the railroad bridge, Mr. Simmerson said, and these big

guns mowed down trees on the Rowan side of the river...."69 If Stoneman had any hopes of a

surrender at the Yadkin, they were dashed when "York sent him word that

he would hold the works against 10,000 Yankees."70 Col. John K. Miller's brigade arrived at the river about 2:00.71 Miller's brigade was made up of the 8th Tennessee and 13th Tennessee,72 and numbered 1,000 men.73

A Union officer approached the bridge on horseback to survey the

situation. "The officer was promptly shot off his horse."74 "At the first advance, so the older inhabitants say, sixteen of the blue coats were killed or mortally wounded."75 Miller sent back to Salisbury for the artillery, which arrived about 3:00.76

Stoneman's artillery battery carried with them four Parrott guns (Peter

Cooper, Professor of Anthropology at Catawba College has found a

fragment of Parrott shells at this site), and possibly a few other

pieces.77 "18 pieces of artillery with caissons, forges, and battery wagons complete"78

had been captured earlier in the day at Grant's Creek. Both

Confederate and Union forces had access to the ammunition at the

Salisbury armory. The stage was set for an all-out artillery

assault - the Union blue on the south (Rowan) side of the river, the

Confederate gray on the north (Davidson). Margaret Beall Ramsey recorded,

"A strong force concentrated to attack this railroad bridge.

Heavy cannonading at the river bridge continued until dark [7:30].79

The raiders, thinking the bridge too strongly fortified returned to

Salisbury, destroying the railroad as they went. A few

Confederates were wounded, and one or two killed."80 The Confederates "had their

well-placed cannon, shooting solid shot of great dimension, backed by

withering rifle barrage from their impregnable fortress, so that

Stoneman's men gave up their assault as a bad job and turned back ...."81 One Tennessean who was there called it "a sharp fight which compelled them to retire."82 The following morning,

"Stoneman's pursuing cavalry was coming back to Salisbury after a

battle lost. But no wild cheers, no war whoops of victory

marked their return to the town. General Beauregard's

defenders had saved the Yadkin River railroad bridge."83 Brenizer wrote that it was "a remarkable thing to relate that 'THEY DID NOT BURN THE BRIDGE!''"84 Several days later, Robert

Herriot, of Bachman's (German) Battery, described the battle's

aftermath: "... In proceeding South we crossed the Yadkin

River on the railroad bridge, which was planked. The river is

deep and narrow, with high banks at the bridge, and here was done most

of the fighting when Stoneman was repulsed. There was much

debris lying around - broken caisons and limbers, dismounted field

pieces[.] I noticed one piece that had been struck on the

edge of the mouth and dismounted."85 The two forces were fairly

evenly matched in number and firepower. But the Confederates

held the advantage of position and fortification. The

earthworks of Camp Yadkin stood the test, and provided the Confederates

with their last victory in North Carolina.

In the Days Following

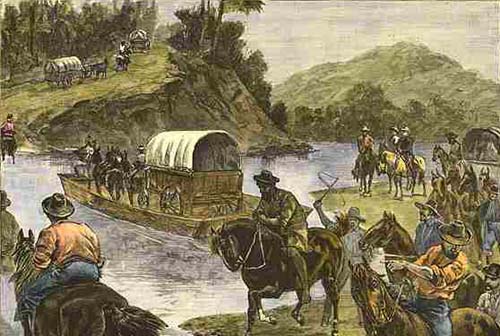

With the Confederacy collapsing

around him, President Jefferson Davis, his Cabinet, and the Treasury

fled south - to Greensboro, Lexington, Salisbury, Concord, Charlotte,

and on to South Carolina and Georgia. On Easter Sunday, April

17, 1865, Davis reached the Yadkin River. The ferryman had

left, and Henry Mills, of Stanly County, was the only man at Camp

Yadkin who could manage a flat. He recalled that "the ferry

was 150 yards from the railroad bridge." (This distance could

refer to either the Yadkin Ford ferry below the railroad bridge or the

Confederate ferry above it.) Mills recalled ferrying 500

horsemen and an ambulance carrying a red-haired woman with three

children, whom he mistook for Davis' family. "The President

was the last one to go over. He asked me to be careful and

not touch his horse with the pole. He did not speak to me as

an inferior, but very kindly as to a friend. Oh, how we boys

did love him. When we got safely over the river, he thanked

me and gave me a silver dollar which I have always kept."86 This scene was captured by an artist for the Illustrated London News.87 With the Confederacy collapsing

around him, President Jefferson Davis, his Cabinet, and the Treasury

fled south - to Greensboro, Lexington, Salisbury, Concord, Charlotte,

and on to South Carolina and Georgia. On Easter Sunday, April

17, 1865, Davis reached the Yadkin River. The ferryman had

left, and Henry Mills, of Stanly County, was the only man at Camp

Yadkin who could manage a flat. He recalled that "the ferry

was 150 yards from the railroad bridge." (This distance could

refer to either the Yadkin Ford ferry below the railroad bridge or the

Confederate ferry above it.) Mills recalled ferrying 500

horsemen and an ambulance carrying a red-haired woman with three

children, whom he mistook for Davis' family. "The President

was the last one to go over. He asked me to be careful and

not touch his horse with the pole. He did not speak to me as

an inferior, but very kindly as to a friend. Oh, how we boys

did love him. When we got safely over the river, he thanked

me and gave me a silver dollar which I have always kept."86 This scene was captured by an artist for the Illustrated London News.87

President Davis soon reached

Salisbury, where the remains of Stoneman's fiery devastation still

smoldered. No one offered an invitation for the distinguished

guest, until he was taken in by Thomas G. Haughton, rector of St.

Luke's Episcopal Church.88

On the 18th, he sent a telegram from Salisbury arguing against

disbanding "the battalion of Virginians now at Camp Yadkin."89

Evidently at least some of York's forces were disbanded, for Henry

Mills recalled Company I, supporting forces of men over 45 from Anson,

Stanley, Montgomery, Moore, Chatham, Randolph, and Davidson counties,

being disbanded that day.90

When the Confederate forces in North Carolina finally capitulated

several weeks later, the 40th Alabama Infantry, consolidated with the

19th and 46th, was surrendered at the Yadkin River bridge.91 Although word didn't reach the

south immediately, the day following Stoneman's departure from

Salisbury was the momentous day of Abraham Lincoln's assasination at

Ford's Theater. The entire nation, north and south, soon

reverberated with shock. As the war finally ended,

Salisbury was occupied by U.S. Troops. Beaten, devastated,

and impoverished, the south began the long, slow process of

recovery. The stories of what happened at Grant's Creek,

Salisbury, and Camp Yadkin were nearly forgotten under the dust of the

past.

The author gratefully acknowledges Wayne Boone, Chris Hartley, and Steve Walters for their painstaking research and assistance!

© 2003, Ann Brownlee

Notes

1 Wood

2 Ramsey

3 Van Noppen; Hartley, 1990 and 1998; Boone

4 Brawley, 1/8/1964

5 Brown

6 Hartley, 1998; United States, War Department (hereinafter referred to as OR), 1-47-III p. 791

7 Hartley, 1998

8 Van Noppen; Hartley, 1990 and 1998; Boone

9 First light on April 12, 1865 occurred about 5:30 a.m. U. S. Naval Observatory

10 Brig.

Gen. Alvan Gillem reported the Confederate forces at 3,000, with 18

pieces of artillery. He reported capturing 18 pieces of

artillery with caissons, forges, and battery wagons complete, 17 stand

of colors, and between 1,200 and 1,300 prisoners. OR

1-49-I p. 324

11 Beall; Hartley, 1998; Stewart

12 Barrett

13 see Gillem's report OR, 1-49-I pp. 333-334

14 Bruner, 4/9/1889

15 OR, 1-49-I p. 333

16 OR 1-49-I p. 333

17 Hartley, 1998

18 100

men of the 11th Kentucky under Lt. Col. Slater were sent up the

creek. Major Donnelly, 13th Tennessee Cavalry with about 100

men was sent below the Old Mocksville Road, and Lt. Col. Smith, with a

party of dismounted men, were sent still farther down Grant's

Creek. OR, 1-49-I p. 333

19 7:30 according to Bruner 4/9/1889; 8:00 acording to Beall

20 OR, 1-49-I p. 333

21 OR 1-49-I pp. 333-334; Spencer

22 Ramsey

23 Bradshaw

24 Wood

25 Old North State 8/11/1871

26 Ramsey

27 Bruner, 4/9/1889

28 Bruner, 4/13/1882

29 Brawley 5/9/1965

30 Bradshaw

31 Dunn

32 OR 1-49-I p. 334

33 Brown

34 Chamberlain

35 Beall

36 Van Poole

37 Gillem reported destroying the following stores:

10,000 stands of arms

1,000,000 rounds of ammunition (small)

10,000 rounds of ammunition (artillery)

6,000 pounds of powder

3 magazines

6 depots

10,000

bushels corn

75,000 suits of uniform clothing

250,000 blankets (English manufacture)

20,000 pounds of leather

6,000 pounds of bacon

100,000 pounds of salt

20,000 pounds of sugar

27,000 pounds of rice

10,000 pounds of saltpeter

50,000 bushels of wheat

80

barrels turpentine

$15,000,000 Confederate money

medical stores, valued at over $100,000 in gold, OR, 1-49-I p. 334

38 Ramsey

39 Brown, p. 174

40 Brawley 6/13/68

41 Bradshaw

42 Chamberlain

43 Brawley 2/15/70

44 Bradshaw

45 Bradshaw

46 OR 1-49-I p. 333

47 Bruner 4/13/1882; Ramsey

48 Ramsey

49 Beall

50 Bradshaw; Beall; Dunn

51 Bradshaw

52 Beall

53 Ramsey

54 Boone

55 OR, 1-39-I, pp. 233-234

56 OR, II-8, p. 212

57 OR, 1-49-I p. 338; OR, 1-49-II p. 331

58 OR, 1-47-III p. 729

59 OR, 1-47-III p. 746

60 OR, 1-47-III p. 791

61 OR, 1-47-III, p. 761

62 Bruner 2/27/1890

63 OR, 1-47-III p. 810

64 Bruner 2/27/1890

65 Beall

66 Bruner 2/27/1890

67 Gwin

68 Gwin

69 Gwin

70 Bruner 2/27/1890

71 Beall

72 OR, 1-47-I p. 325; Boone

73 Boone

74 Gwin

75 Bruner 2/17/1890

76 Beall

77 Brown, p. 175; Boone; OR 1-47-III pp. 740, 747, 752, 756, 757

78 OR, 1-49-I p. 334

79 Ramsey; Dark on April 12, 1865 occurred about 7:30 p.m. U. S. Naval Observatory

80 Ramsey

81 Gwin

82 Barchfield

83 Bradshaw

84 Brown p. 175, Brenizer

85 Herriot

86 Brawley 3/4/2979

87 Illustrated London News

88 Brawley 3/25/1973

89 OR, 1-47-III, p. 810

90 Brawley 3/4/1979

91 Confederate Military History, vol. VIII, p. 180

Bibliography

Barrett, John G., The Civil War in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963.

Barchfield's Memoranda. Arnell Collection, University of Tennessee.

Bealle, Robert Lamar, Personal account reprinted in "Raiders Had Easy Time Until They Reached River." Salisbury Post. April 11, 1965.

Boone, Wayne, "General Stoneman." website published at www.generalstoneman.com, 1999.

Bradshaw, Harriet Ellis, Personal account reprinted in "How a Family Faced Arrival of Stoneman." Salisbury Post. April 11, 1965.

Brawley, James, "Brave Rebel Killed a Yankee on Innes Street." Salisbury Post. February 15, 1970.

Brawley, James, "Eyewitness account of Stoneman's Raid." (Thomas Franklin Safley account) Salisbury Post. Setpember 23, 1979.

Brawley, James S, "History's Footnotes." Salisbury Post. March 29, 1959.

Brawley, James S, "Hospital Was Set Up at Lee & Council." Salisbury Post. July 15, 1962.

Brawley, James, "Jeff Davis Calms a Small Salisbury Child." Salisbury Post. March 25, 1973.

Brawley, James, "Little Girl Cut Down Union Flag." (John I. Shaver account) Salisbury Post. June 20, 1965.

Brawley, James, "Many Confederate Facilities Here." Salisbury Post. February 16, 1964.

Brawley, James, "More Memories of Stoneman." (A. M. Rice account) Salisbury Post. June 13, 1968.

Brawley, James S, "100-Year-Old Granite Bridge as Good as New." Salisbury Post. March 2, 1975.

Brawley, James, Rowan County: A Brief History. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1974.

Brawley, James, The Rowan Story 1753-1953. Salisbury, NC: Rowan Printing Co., 1953.

Brawley, James S, "Salisbury, On Eve of Civil War, Has Finally Tasted of Prosperity." Salisbury Post. January 8, 1961.

Brawley, James, "Stoneman's Raid on Salisbury Recalled." Salisbury Post. March 11, 1973.

Brawley, James S, "Waiting for Stoneman's Yanks." Salisbury Post. March 6, 1960.

Brawley, James, "Watchman's Demise Sign of War's End." Salisbury Post. May 9, 1965.

Brawley, James, "When Jefferson Davis crossed the Yadkin." (Henry Mills account) Salisbury Post. March 4, 1979.

Brenizer, A. G., Captain A. G. Brenizer Papers, Miscellaneous Papers, P.C. 351.1-354 State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

Brown, Louis A., The Salisbury Prison, A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons 1861-1865, Revised and Enlarged. 1992.

Bruner, J. J., ed., Carolina Watchman. March 18, 1875; April 5, 1877; April 19, 1877; April 13, 1882; April 9, 1889; February 27, 1890.

Bumgarner, Matthew, Kirk's Raiders. Hickory, NC: Tarheel Press, 2000.

Casstevens, Frances H., The Civil War and Yadkin County, North Carolina. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997.

Confederate Military History Extended Edition. Vol. VIII Alabama. Confederate Publishing Co., 1899, and Broadfoot Publishing Co., Wilmington, NC, 1987.

Chamberlain, Hope Summerell, This Was Home. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1938.

Cherry, Kevin, "Map of Salisbury Drawn During Battle." Salisbury Post. May 23, 1959.

Currey, Mary Eliza, "The Siege of Salisbury: Girl's Diary Details Invasion of Union Troops 119 Years Ago." Salisbury Post. April 12, 1984.

Davis, Chester S, "Stoneman's Raid Into Northwest North Carolina." Journal - Sentinel, Winston-Salem, NC. October 4, 1953.

Dunn, J. Allan,

"Stoneman's Raid was 69 Years Ago Today and Salisbury Citizen Recalls

Incidents about Ravaging of City." (J. I. Shaver account) Salisbury Post. April 12, 1934.

Gwin, Harry, "Few

Know that Stoneman's Raiders Were Turned Back at Yadkin River." (C. D.

Simmerson, Essie Meares and Mrs. J. T. Yarborough accounts) Salisbury Post. September 2, 1951.

Hartley, Chris J., "Like an Avalanche: George Stoneman's 1865 Cavalry Raid." Civil War Regiments. Volume 6, No. 1 (1998).

Hartley, Chris, "War's Last Cavalry Raid." America's Civil War. January 1990.

Herriot, Robert, Confederate Veteran, Volume 30, p. 102. (quoted by Wayne Boone, "General Stoneman")

"Mr. Jefferson Davis and his

party retreating across the Pee-Dee River, North Carolina, at the fall

of the Southern Confederacy, 1865." Illustrated London News.

December 14, 1889. From the North Carolina Collection,

University of NC Library at Chapel Hill, accessed online:

www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/pcoll/civilwar/81-336.JPG

Old North State, The. August 11, 1871.

Ramsey, Bargaret Beall, "Reminiscences of Harrowing Days in Salisbury." Salisbury Post. September 25, 1932.

Raynor, George, Rebels and Yankees in Rowan County. Salisbury, NC, 1991.

Salisbury Post. "Today 88th Anniversary of Stoneman's Raid on City." April 12, 1953.

Shiman, Philip, "Fort York: A Late War Confederate Fort on the Yadkin River." c. 1988.

Sneden, Private Robert Knox, Eye of the Storm, A Civil War Odyssey, Charles F. Bryan, Jr. and Nelson D. Lankford, Eds. New York: Simon & Schuster, ©2000 Virginia Historical Society (online at www.sneden.com)

Shober, May Wheat,

Personal account reprinted by James Brawley. "Yankee

Prisoners Freed with a Vengeance." Salisbury Post. November 14, 1976.

Sneden, Robert Knox, et al, Eye of the Storm. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Spencer, Cornelia Phillips, Last Ninety Days of the War. New York: Watchman Publishing Co., 1866.

Stewart, J. J., editor of the Daily Banner, Reprinted by James Brawley. "April 1865, Recalls City's Saddest Days." Salisbury Post. April 29, 1973.

U. S. Naval Observatory, "Sun and Moon for One Day", accessed online http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneDay.html

United States, War Department, Record and Pension Office, War Records Office, et al, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895-1897.

Van Noppen, Ina Woestemeyer, Stoneman's Last Raid. Raleigh: NC State College Print Shop, 1961.

Van Poole, Dr. C. M.,

"Why Rowan Courthouse Escaped Burning When Stoneman Raided Salisbury in

1865 Recalled." Salisbury Post. December 18, 1932.

Wood, William Nicol, as told to

his granddaughter Mary E. Gandy, "Salisbury

Recollections." 1964.

|